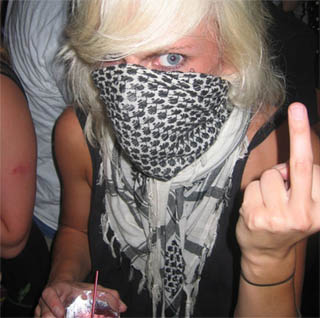

For some months now, I've been reading about the hipster trend of wearing Palestinian headdresses or keffiyeh as neck scarves. It's only recently that I've begun to see kids in Melbourne doing it too.

Let's set aside the well-known debates over cultural and political appropriation, because they've been rehearsed so many times before when it comes to hip-hop apparel, bindis, dreadlocks, Thai fisherman pants and any number of other 'ethnicised' forms of clothing. I mean, I have always been a little shocked when I saw non-Palestinians wearing keffiyeh because I've always thought of it as a religious as well as an ethnic and political thing. But who am I to talk? I was at a tiki party last Sunday wearing a tropical print 50s-style dress and a lei, drinking rum punch out of a coconut and watching my friends' pitiful attempts at hula dancing.

No: here I am more interested in the transnational flows of hipster cultural capital. Blue States Lose has wondered many times, in its usual tone of laconic despair, how it happens that hipsters somehow 'know' how to be hipsters without ever 'learning' it. I began thinking about this after reading this blog post about a magazine series on the 'flashmobbing' fad, and the ensuing comments.

As Bill Wasik writes in the article,

hipsters, our supposed cultural avant-garde, are in fact a transcontinental society of cultural receptors, straining to perceive which shifts to follow. I must hasten to add that this is not entirely their fault: the Internet can propagate any flashy notion, whether it be a style of eyewear or a presidential candidacy, with such instantaneity that a convergence on the “hip” tends now to happen unself-consciously, as a simple matter of course.For Wasik, this is the essential paradox of hipsterism: that a culture predicated on aesthetic individualism could be so homogenous and susceptible to fads. And according to Wasik's logic, the Palestinian keffiyah craze, like the popularity of McSweeney's, Interpol and black stovepipe jeans, is all about the internet.

But I am not about to celebrate the transnational information flows enabled by technology. Rather, I am interested in a rather more low-tech idea: that hipsters work out what to do next using their general worship of that altar of cool, "the street". I am interested in the physical congregation of people, the ways their bodies occupy physical space, and the strategies they have of displaying themselves and of observing and interacting with others. If the internet is involved, it's using blogs, email, MySpace and messageboards - technologies that play off and replicate face-to-face networks.

And, importantly, I think these events and technologies are governed by affective relations. In his comments, Doug reflects the commonsense understanding of what it means to be 'cool':

But are hipsters permitted to 'feel' anything? Isn't it a bit twee to feel? [...] how, then, do hipsters manage to be simultaneously 'cool' - universally depicted as being slightly detached from normal worries and concerns - and yet be affected by their cultural consumption?I blame Fredric Jameson and his famous essay on postmodernism for the 'commonsenseness' of the equation: "irony = lack of affect". Detachment isn't a lack of affect: it is an affect; and it requires a certain repertoire of performances and knowledges. Hipster irony generates a variety of affective registers including the pleasure of feeling 'cool', the humiliation of exclusion and the outrage of moral violation.

Importantly, hipsterism is private yet public, just as irony relies for its meaning on a privately understood but publicly unacknowledged other meaning. I think that this, and not the nihilism that is often ascribed to hipsterism, is why it is incapable of politicisation. Politics relies on convincing an ignorant or uncaring audience of the importance of a topic: it's insiders talking to outsiders. Hipsterism is insiders talking to insiders, and that's why its aesthetics are apolitical.

Or rather, hipsterism has only a base, brain-stem politics: it delights in the event, in the idea of togetherness, even if that togetherness serves only hedonistic purposes. There is a primitive kinship in the idea of seeing someone wearing a keffiyeh, identifying them as 'cool', and deciding that you want to be cool, too.