In the original 1865 John Tenniel illustrations, her clothes grow and shrink with her.

But viewing the affectingly mended pioneer-lady "best dress" in the Darnell Collection, which was so delicate it's displayed flat in a glass case, made me think of Little House In The Big Woods by Laura Ingalls Wilder. As a kid I loved the Little House books for their blow-by-blow descriptions of pioneer homemaking and everyday life. This was such a vastly different world to the one I was growing up in that it might as well have been another planet.

The book has been digitised for Canada's Gutenberg Project, so you can read the whole thing online. It also includes Helen Sewell's illustrations, which I think were added some time between 1943 and 1953. The part that has always stayed with me is when they make maple sugar at Laura's grandparents' house.

Pa's blue eyes twinkled; he had been saving the best for the last, and he said to Ma:The book is set around 1870. At this time fashion in the United States was about a year behind Europe, and in pioneer Wisconsin I'd imagine it was further behind still. Caroline married Charles Ingalls in 1860 and her delaine (the word means a light, smooth wool fabric; it's from the French mousseline de laine, muslin of wool) probably dated from the late 1850s.

"Hey, Caroline! There'll be a dance!"

Ma smiled. She looked very happy, and she laid down her mending for a minute. "Oh, Charles!" she said.

Then she went on with her mending, but she kept on smiling. She said, "I'll wear my delaine."

Ma's delaine dress was beautiful. It was a dark green, with a little pattern all over it that looked like ripe strawberries. A dressmaker had made it, in the East, in the place where Ma came from when she married Pa and moved out west to the Big Woods in Wisconsin. Ma had been very fashionable, before she married Pa, and a dressmaker had made her clothes.

The delaine was kept wrapped in paper and laid away. Laura and Mary had never seen Ma wear it, but she had shown it to them once. She had let them touch the beautiful dark red buttons that buttoned the basque up the front, and she had shown them how neatly the whalebones were put in the seams, inside, with hundreds of little crisscross stitches.

I also loved the part in which Laura's two young aunts Docia and Ruby are getting ready for the sugar dance.

They helped each other with their corsets. Aunt Docia pulled as hard as she could on Aunt Ruby's corset strings, and then Aunt Docia hung on to the foot of the bed while Aunt Ruby pulled on hers.I've selected this extended excerpt because it's so rich with detail: not only about the dresses and underwear themselves but the physical ideal of the tiny waist. Of course, Ingalls Wilder isn't an especially reliable narrator because she is recalling events of decades earlier, but the way that Docia "gasps" yet is still dissatisfied with her waist says a lot about the way that perhaps even its own wearer's uncorseted body wouldn't have fitted into one of these dresses. Yet Caroline still fits into her delaine dress after having borne three children."Pull, Ruby, pull!" Aunt Docia said, breathless. "Pull harder," so Aunt Ruby braced her feet and pulled harder. Aunt Docia kept measuring her waist with her hands, and at last she gasped, "I guess that's the best you can do."

She said, "Caroline says Charles could span her waist with his hands, when they were married."

Caroline was Laura's Ma, and when she heard this Laura felt proud.

Then Aunt Ruby and Aunt Docia put on their flannel petticoats and their plain petticoats and their stiff, starched white petticoats with knitted lace all around the flounces. And they put on their beautiful dresses.

Aunt Docia's dress was a sprigged print, dark blue, with sprigs of red flowers and green leaves thick upon it. The basque was buttoned down the front with black buttons which looked so exactly like juicy big blackberries that Laura wanted to taste them.

Aunt Ruby's dress was wine-colored calico, covered all over with a feathery pattern in lighter wine color. It buttoned with gold-colored buttons, and every button had a little castle and a tree carved on it.

Aunt Docia's pretty white collar was fastened in front with a large round cameo pin, which had a lady's head on it. But Aunt Ruby pinned her collar with a red rose made of sealing wax. She had made it herself, on the head of a darning needle which had a broken eye, so it couldn't be used as a needle any more.

They looked lovely, sailing over the floor so smoothly with their large, round skirts. Their little waists rose up tight and slender in the middle, and their cheeks were red and their eyes bright, under the wings of shining, sleek hair.

Ma was beautiful, too, in her dark green delaine, with the little leaves that looked like strawberries scattered over it. The skirt was ruffled and flounced and draped and trimmed with knots of dark green ribbon, and nestling at her throat was a gold pin. The pin was flat, as long and as wide as Laura's two biggest fingers, and it was carved all over, and scalloped on the edges. Ma looked so rich and fine that Laura was afraid to touch her.

Perhaps their diet has something to do with their body shapes? Later in the same chapter, the author remarks, "They could eat all they wanted, for maple sugar never hurt anybody." Really? Ingalls Wilder's descriptions of food are quite interesting throughout; often they sound spartan to a modern reader.

Wisconsin: A History, by Robert Nesbit and William Thompson, notes that: "The recollection of food or the want of it is a common feature in pioneer reminiscences", and that pioneers who'd made it through bad winters joked darkly that they couldn't change their shirts for months, "the fish bones sticking through and preventing such an operation."

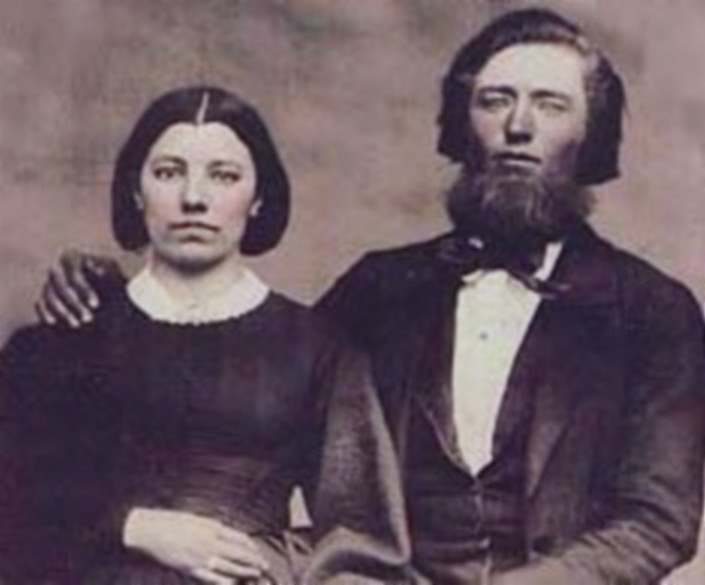

Caroline was a pretty woman, wasn't she? As for Charles… well, I guess Abe Lincoln beards were really in at that time.