Several garments that resemble modern women's underwear were found in a vault filled with layers of dry material – straw, twigs and wood, but also leather (old shoes) and textiles (old clothes). They could have been thrown in there simply to dispose of them, or to level the floor when a second storey was added to the castle in the 1480s.

The textiles range from complete, well-preserved linen and wool garments to fragments. Some belonged to men, while the small cuff circumference on some of the shirts suggests they were worn by women or children. Basically, it's a complete fluke that this stuff has survived to the present, a quirk of the dry archival conditions in which it's inadvertently been stored.

But you wanna know about the bra, right? Well, there were four items resembling contemporary bras. Two of them were kind of like crop tops; they end right under the breasts, but cover the decolletage. These were trimmed with lace along the hems. A third garment had broad shoulder straps that widen into the cups like a halter-neck top, and was elaborately decorated with lace on the straps, between the cups and along the hem.

What makes them most like contemporary bras is the use of tailored cups, rather than a simple flat band across the breast, as worn in ancient Greece and Rome.

This mosaic from the Villa Romana del Casale in Sicily is often dubbed the 'bikini girls' for obvious reasons, but these women are clearly athletes and their 'bikinis' look much more like contemporary elite running apparel.

This is Melissa Breen, currently Australian 100m and 200m champion and soon to represent Australia at the London Olympics.

But anyway, the fourth garment is the one that most resembles a modern bra, and is the one most frequently depicted in the current media coverage. It extends to the bottom of the ribcage, and there's an extant row of eyelets on the left side in which laces would be inserted to fasten it.

Most of the torso and back is missing, so it's unclear how it originally looked. But what annoys me is the photo comparing this garment to a 1950s-style longline bra, as if to suggest that's how it would have looked when intact.

You can see the two garments aren't even cut the same way! (The medieval garment has vertical seams down the centre of the cups.) And what might look to us like a low-cut cleavage might well be an accident of where the 15th-century linen has torn over time.

We often try to make these connections through time to make history seem less distant, much as we call the Roman athletes 'bikini girls'. Because the older garment looks like its modern equivalent, we see them as a teleological trajectory of fashion, with our own garments as the logical and most 'evolved' version.

For instance, a 1932 feature article in the Chicago Sunday Tribune located the corset's 'origin' in the image of the bare-breasted Minoan snake goddess, despite the fact that Minoan art also depicted slender waists on men who are not wearing corset-like bodices.

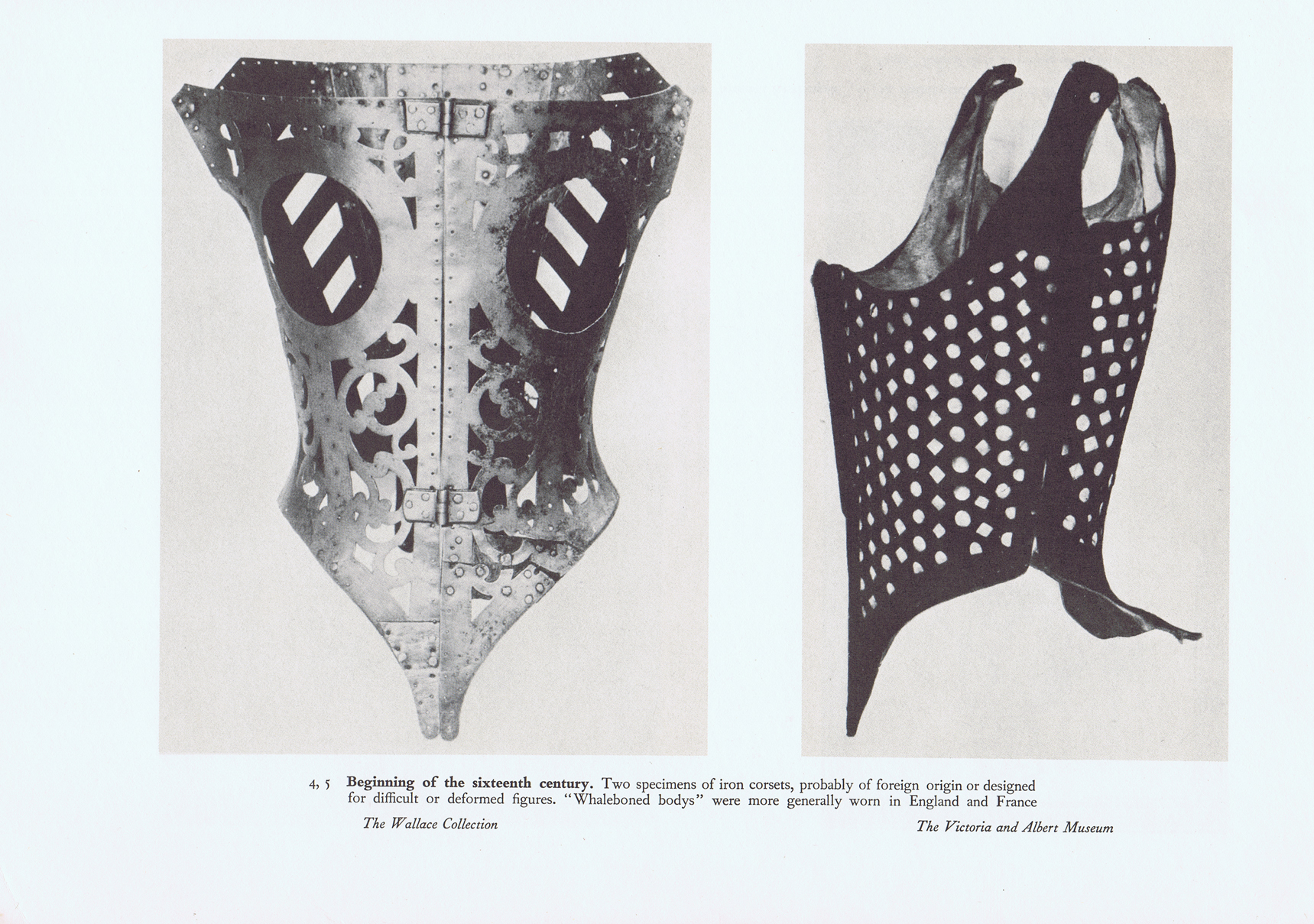

The same article contrasts what was then the modern corset, “a subtle, supple thing of silk and elastic”, with the corset of yore, “a torturous device of leather and steel”. Trouble is, metal corsets were almost certainly orthopaedic – meant to correct deformed bodies.

Of course, we now see 1930s corsets as restrictive. It seems to be human nature in every era to interpret the clothes of the past as 'primitive' versions of our own familiar apparel.

So basically, the Lengberg textiles are not "the world's oldest bra", and they don't prove that bras were "invented" 500 years earlier than we thought. While they might serve a similar sartorial function to a bra, they are completely separate garments with their own cultural context. So… what might that be?

The huge significance of this Austrian find is that it's the first extant medieval underwear. Until recently, our ideas of medieval clothing came only from illuminated manuscripts and artworks, from literature, and from written records such as clothing inventories or receipts, wills (clothing was often bequeathed, but you wouldn't give your undies to your heirs!) and the rules of religious orders.

For instance, while regulations on monks' clothing mention shirts, stockings/hose and under-breeches (known as braies), chemises and stockings are the only underwear listed as being allocated to nuns, leading us to conclude they didn't wear anything else. This is also borne out in E Jane Burns' analysis of gender and underwear in the French Prose Lancelot.

Burns quotes one instance in Chrétien de Troyes's Le Chevalier de la Charrette (c1180) where a damsel being ravished is "villainously held down … uncovered to the waist." This means she's not wearing any drawers under her chemise.

But what about on the top half?

Christina Frieder Waugh writes (PDF link) that in medieval poetry, a beautiful woman's breasts were often described as being "hard as little apples". Umberto Eco's much-cited book Art & Beauty in the Middle Ages quotes Gilbert of Hoyland's Sermones in Canticum Salomonis, on ideals of feminine beauty:

The breasts are most pleasing when they are of moderate size and eminence…they should be bound but not flattened, restrained with gentleness but not given too much licence.The same Gilbert of Hoyland who had such definite opinions on women's breasts was a 12th-century English Cistercian abbot. Waugh quotes him advising his monks to practise restraint, much as women restrain their boobs!!

For what are they more anxious to avoid in embellishing the bosom, than that the breasts be overgrown and shapeless and flabby? … Therefore they constrain overgrown and flabby breasts with breast-bands, artfully remedying the shortcomings of nature.And in the Romance de la Rose, a 13th-century poem by two authors, the Old Woman character offers what's basically a medieval French version of Cosmo magazine advice:

And if her breasts are too full, let her take a kerchief or scarf and wrap it round her ribs to bind her bosom, and then fasten it with a stitch or knot; she will then be able to disport herself.Beatrix Nutz, a University of Innsbruck archaeologist who's writing her thesis on the Lengberg textiles, cites French royal surgeon Henri de Mondeville's description, in his Cyrurgia: “Some women… insert two bags in their dresses, adjusted to the breasts, fitting tight, and they put them [the breasts] into them [the bags] every morning and fasten them when possible with a matching band.”

A satirical poem by an unknown 15th-century German author also refers to "breastbags" or "bags for the breasts":

…with them she roams the streets, so that all the young men that look at her, can see her beautiful breasts; But whose breasts are too large, makes tight pouches, so there is no gossip in the city about her big breasts.What's interesting is that the 'bags' here seem more structured than a band, and also adjustable to the size of the breasts. Perhaps the greatest cultural similarity between contemporary bras and the Lengberg textiles is that in the 15th century, large breasts were interpreted as excessive and licentious – much as they are now.