For a start, I rarely find anything that fits me in a vintage shop. That was the catalyst for my current book project. Second – and more importantly – I feel very worried about being judged sartorially by people who are much more into vintage than I am. The vintage subculture feels like a club whose membership can instantly be extended or denied with a single assessing look at someone's outfit.

As well as Jaunty Pussy, I would call my dress sense 'low retro'. That is, I am inspired by looks ranging from the 1950s to the 1970s, I own a lot of preppy, old-fashioned clothes, wear winged eyeliner and browline glasses most days, and I guess Stam is an old-fashioned frame handbag. But I don't aim for period-accuracy, and I usually mix the retro stuff up with contemporary items.

On an evening last April I found myself on a tram sitting opposite a 'high retro' chick. She had a rolled fringe and was wearing a cardigan over a red, white and blue striped sailor-esque outfit. The dark regrowth in her blonde hair, her set face and harsh, heavy makeup reminded me of a '40s working-class girl – like something from Come In Spinner, Summer of the Seventeenth Doll or Caddie.

I could see her suspiciously eyeing my low-retro getup: my glasses and eyeliner; button-through floral frock, cardigan and bag. I felt as if she were judging me on her standards, and deciding that I had tried and failed to be high retro.

So I am very intimidated about what to wear on Friday to the opening night of Love Vintage, as there will be a 'best dressed' fashion parade and I imagine everyone there will be pulling out their best looks. Unfortunately, I pulled the trigger on my own best look too early; I wore it to a country vintage fair last Sunday.

I took my parents, and it was a lovely Mother's Day outing, but to be honest I was disappointed by the small scale of the fair, and I felt embarrassed that I'd got dressed up, because the only other people dressed like me were Miss Lulu and Miss Ruby Rabbit, the pinup hairdo ladies, and Lauren Randle of Castlemaine vintage store The Reclaimed Room. I had a nice chat with Lauren, though.

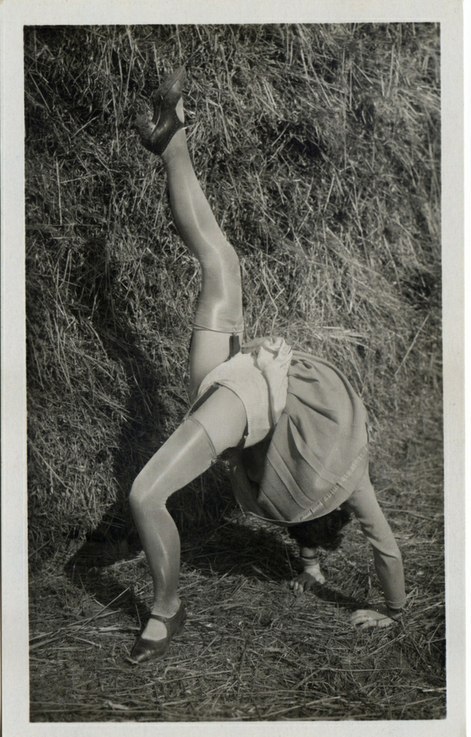

Today I was looking through my wardrobe and fretting that nothing in there looked high retro enough. I started pulling dresses out and laying them on the bed and then laying necklaces and cardigans on top, and then I started fiddling with my hair, and then ultimately this is what I ended up wearing today:

I am not trying very hard. I didn't bother to straighten my fringe or curl my hair; I just did victory rolls, which is incredibly easy once you get the hang of it; these ones don't even have any hairspray fixing them in place.

The look is vaguely 1940s, I suppose. It's hard to see in the photo, but my teal blouse matches the sequins on my cardigan. The blouse has puffed sleeves and lots of pintucks along the shoulder seams, and is tucked into a pair of high-waisted black harem pants. I'm also wearing my half-wingtips, half-sneakers, which I got from a Richmond garage sale recently for $5.

I am still low retro, but I'm climbing a little higher than usual. Hopefully by Friday I will be high enough to pass muster among the hardcore vintage aficionados.