ThreeThousand is advertising its Christmas party using a doctored image from The Breakfast Club. I couldn't help noticing the startlingly contemporary way Molly Ringwald is dressed in that film. She wears a white lace neckerchief, a loose-fitting pink V-necked t-shirt with the sleeves rolled up, tucked into a high-waisted chocolate brown knee-length skirt, and brown knee boots. You can see fashionably dressed women wearing variations on this outfit right now. I guess I found this particularly striking today, given that I'm wearing a neckerchief, a high-waisted knee-length skirt, and knee boots.

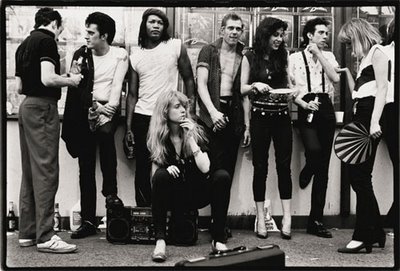

Around the same time ThreeThousand began advertising its party, I was sent a link to a marvellous slide show based on Amy Arbus's book On the Street, a collection of photographs from 1980-1990, which ran in Arbus's column of the same name in The Village Voice. Again, I was struck by the contemporaneity of the image of The Clash in 1981. You could find people in Melbourne right now dressed just like those people from 1981. It looks like an ad for jeans, except they'd never have allowed the non-jeans-wearing dude on the far left into the frame.

Why do these clothes look contemporary? I'm troubled by the distinct possibility that an ironic nostalgia is what's inspiring contemporary kids to dress like the ones in the photos, and what inspires companies to sell that nostalgia to us as lost authenticity. Because let's face it; we're talking about hipsters, and so we must tackle irony. And where there are hipsters, there are clothing manufacturers who believe in the authenticity of these hipsters' cultural activities, and want to jump on their bandwagon in order to market their clothes successfully to people who want the feeling of cool that self-perceived authenticity imparts.

Coined in the seventeenth century to describe a pathological homesickness, nostalgia has come to denote the pang that accompanies the impossibility of returning to an idealised past. In her book On Longing, Susan Stewart argues that nostalgia devalues the lived present, making the idealised past the site of authenticity. She defines nostalgia as "the repetition that mourns the inauthenticity of all repetition". Looks like she's getting all Jamesonian on our arses.

In his oft-cited Postmodernism, or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism, Fredric Jameson writes that the nostalgic turn arises from "the enormity of a situation in which we seem increasingly incapable of fashioning representations of our own current experience". What Jameson calls "the nostalgia form" of postmodern culture "approaches the 'past' through stylistic connotation, conveying 'pastness' by the glossy qualities of the image, and ... by the attributes of fashion". So here, we're talking about "80s-ness".

For Stewart, its utopianism gives nostalgia an innocence very unlike the self-awareness of irony, while Jameson conflates nostalgia and irony (in the form of pastiche) as equally self-aware and destructive products of the postmodern condition. But Linda Hutcheon argues that nostalgia and irony are strikingly similar, because both have doubled meanings. Nostalgia reveals both an unsatisfying present and an idealised past, while irony offers both said and unsaid meanings.

"What irony and nostalgia share, therefore, is a perhaps unexpected twin evocation of both affect and agency", writes Hutcheon. Neither inheres in a text – they’re something that the body makes happen.

As a sense of real time and history becomes lost in the postmodern morass, Jameson argues that the unified modern subject becomes fragmented and loses the capacity truly to feel -- his famous "waning of affect". Jameson doesn't, however, suggest that feelings are altogether absent from postmodern culture: rather, they become "intensities" that are "free-floating and impersonal ... dominated by a peculiar kind of euphoria" and anxiety that Jameson likens to the sublime.

But for Hutcheon, nostalgia doesn't destroy affect -- it is an affect.

... nostalgia is not something you "perceive" in an object; it is what you "feel" when two different temporal moments, past and present, come together for you and, often, carry considerable emotional weight. ... it is the element of response -- of active participation, both intellectual and affective -- that makes for the power.

So first imagine you're a hipster. You look at these images and you get excited. You're meshing these images of the past with the contemporary trends you see around you. You're imagining how you'll harness the past, how you'll look wearing these clothes. You'll imagine yourself being Molly as she gives generationalism the finger on one special Saturday. You'll imagine yourself lounging suavely like The Clash. But you'll be doing this now. Then imagine you're a marketer or a fashion designer looking for the next source of inspiration. And you trawl backwards, looking for that thing that'll get you excited. Because making the past seem fresh is your job.

Are you doing this in a thoughtless and facetious way? No, argues Hutcheon. "The ironizing of nostalgia, in the very act of its invoking, may be one way the postmodern has of taking responsibility for such responses by creating a small part of the distance necessary for reflective thought about the present as well as the past."

But it seems to me as though these are two kinds of nostalgia at play here: The Breakfast Club speaks to a mediatised nostalgia; what Hutcheon delightfully calls "commercialized luxuriating in the culture of the past". But On the Street, while also mediatised, speaks to something different -- a spatial nostalgia; a nostalgia of the street. I'm intrigued by Jameson's contention that, since the postmodern subject has lost track of temporality, "I think it is at least empirically arguable that our daily life, our psychic experience, our cultural languages, are today dominated by categories of space rather than by categories of time, as in the preceding period of high modernism".

I want to envisage "the street" as one of these categories of space. It's worthwhile remembering that nostalgia in its original sense was a longing for place. Perhaps when nostalgia seeks authenticity, it's discursively creating the street as that authentic space. And perhaps that's why marketers still look to "the street" in their quest to render the old new again. And perhaps that's why people collapse images of the past onto spaces of the present in order to create their personal styles.

This post is part of my thinking-through the paper I'm writing. I welcome your thoughts, because I am really cutting it fine now. I leave town on Tuesday morning...