Today I was reminded of my lost article when reading this piece about innovations in the t-shirt market. I was particularly struck by its entrepreneurial streak: the point seems to be to identify trends to rip off in other markets. But I am interested in the closing section: "Blurring the lines between conventional displays and selling methods may well mirror your customers' blurring perceptions of what constitutes value, or experience."

But as I see it, the success of the brands mentioned in the article doesn't just suggest a blurring of retail convention. It's about changing the basic relationship between product, seller and buyer. As Meaghan Morris writes in her classic essay "Things to Do With Shopping Centres", "it isn't necessarily or always the objects consumed that count in the act of consumption, but rather that unique sense of place"; and I guess what I want to do with this post is to use these examples of new t-shirt marketing as a sort of "place-making" - and as an antidote to the idea of t-shirts as "designer fashion".

The paradox of the "t-shirt label" is that a generic, banal, mass-produced garment takes on what Walter Benjamin would call an 'aura'. In my favourite part of Morris's essay, she dismantles this possibility:

The commodities in a discount house boast no halo, no aura. On the contrary, they promote a lived aesthetic of the serial, the machinic, the massreproduced: as one pair of thongs wears out, it is replaced by an identical pair, the same sweatshirt is bought in four different colours, or two different and two the same; a macrame planter defies all middle-class whole-earth naturalness connotations in its dyes of lurid chemical mustard and killer neon pink. Second, commodity boudoir-talk gathers up into the single and class-specific image of the elite courtesan a number of different relations women and men may invent both to actual commodities, the activity of combining them and, above all, to the changing discursive frames (like shopping centres) that invest the practices of buying, trafficking with and using commodities with their variable local meanings.

So, taking my cue from Morris, I want to sketch several "things to do with t-shirts". And importantly, the new "things" being done with t-shirts are succeeding because they create new spaces that manage to make the t-shirt simultaneously special and generic. First, there's customisation, in which the buyer alters the structure and look of the t-shirt in various ways. Then there's merchandising, in which the t-shirt itself remains unchanged; it's how the buyer interacts with its retail environment that constitutes innovation. Such merchandising techniques are what Morris would call a "discursive frame" - they infuse shopping with meaning.

Clothing customisation has long been understood as a grassroots practice of bricolage - changing the meanings of clothes through a judicious and unexpected alteration of pre-existing items. Journalists still tend to get excited about its possibilities for creativity and individuality. I think the absurdity of such a stance is encapsulated in this phrase from NZGirl: "The only way to achieve individuality is by customising, and we're going to show you how..."

But I'm more interested in the place customisation occupies in the market. For instance, I have customised a number of my old Bonds t-shirts by cutting off the sleeve bands, altering the necklines, ruching the sleeves and reattaching the sleeve bands in different places. But were I to try and sell them, Bonds would get up in my grill about it. When I interviewed Dylan Martorell, who in March 2004 was running Outskirts T-Shirt Gallery, he had this to say:

Mel: What would you do if someone came in with a seriously ordinary t-shirt that looked like they’d just taken a texta to a Bonds t-shirt in their bedroom?

Dylan: And it was good or bad?

Mel: And it was really bad.

Dylan: Well, for a start we wouldn’t stock it because it was Bonds. Um, Bonds are about the only brand that actively, uh, go out of their way to stop people using their t-shirts.

Mel: Oh really?

Dylan: Yeah, I think every other t-shirt brand is happy for their t-shirts to be used, but not Bonds. We’d just tell them we weren’t interested, I guess. That it wasn’t right for the store.

Contrast the attitude of Bonds, a company that seeks to protect its brand from being 'ruined' by customisation, with American Apparel, a company that makes being generic its major selling point. American Apparel began as a wholesale business, selling t-shirts to artists, designers, bands and anyone else who needed a wearable canvas to print on. The company's selling points are quality, fit (slim fit - is it any surprise its biggest customers are hipsters?) and a rainbow of colours.

But I do want to get away from the 'wearable canvas' idea, because it perpetuates the t-shirt label mentality that t-shirts are 'works of art in the age of mechanical reproduction'. Instead, let's look at two ideas that treat t-shirts as commodities in the most obvious way: by inserting them into the retail logics of entirely separate industries.

But while Neighborhoodies is a customising shop, plain and simple, I'm more interested by the food/fashion pun on 'freshness' employed by the T-Shirt Deli. Here, customising is a ritual of performing the 'fresh'. Rather than making your own sandwich at home, you go to a deli, and you feel more virtuous for resisting the temptations of the bain-marie. Moreover, you verify the freshness and healthiness of your lunch (and thus, your virtue) by seeing it made before your eyes. In a similar way, you go to the T-Shirt Deli because you want a product that could have been made by you. You feel better about yourself (more original, individual - more like a bricoleur) because you didn't just buy a pre-sloganed t-shirt. You thought up a witty catchphrase yourself. And the slogan looks especially good to you because it's being assembled right in front of you.

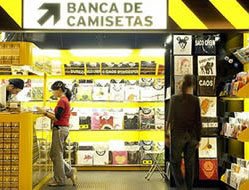

Brazilian store Banca de Camisetas(translation: T-Shirt Stand) is a kind of t-shirt newsagent. There are currently five ‘bancas’ in Sao Paulo. The merchandise is arranged in racks like magazines, the stock is changed weekly, and the store only carries three of each design. The ‘publishers’ are freelance graphic designers; from these photos, the shirts look a lot like the sort of stuff you can find at the T-Shirt Barn in Newtown, Sydney.

But the intriguing thing about Banca de Camisetas is that, while its merchandise fits squarely into the 'art' aesthetic of the 't-shirt line', it isn't sold in a 'gallery' environment and the t-shirts are packed into squares. Instead, there's an accessible, 'convenience' mentality - just as you would in a magazine shop, you're encouraged to 'drop in', to browse, to choose quickly and to return often. I really like the way it refuses to treat the t-shirts as fetishes.

However. Another thing that struck me is that the packaged shirts look almost like records, which in turn connotes another kind of retail fetishism - that of the hip, intense, mostly male vinyl hound spending hours browsing in music stores for rare discs. In every city there's a cartography of subcultural space marked out by spaces like these, and continually reinscribed by DJs and record enthusiasts. For example, in his article on death metal, "It'll All Come Out in the Mosh", Dominic Pettman refers to certain Melbourne metal record shops as the "Devil's Triangle".

The good people at Springwise "can't really think of any big city where this would NOT work!" I agree. It's a great idea. But my contention is that a 'banca' would work in different, locally specific ways in different cities, because people would incorporate it into their existing repertoire of retail techniques. As Morris writes, if a company can create a sense of place, they can market a very banal product with great success.